Meet our amazing mygalomorph, discover its life cycle and learn how to find it

The scarce Purse Web Spider (Atypus affinis) is rarely seen because it spends the majority of its life underground in a sock-shaped tube. In the UK it has the honour of being our only member of the mygalomorph family, which elsewhere includes tarantulas.

Purse Web Spiders normally lead a solitary existence in a silk-lined burrow. The top portion of this tube extends above ground and is extremely well camouflaged with its surroundings, covered with bits of vegetation and debris. Most of the time this tube is completely sealed.

When the Purse Web Spider’s prey makes contact with the exposed section of burrow the spider senses its vibrations and bites through the silk with its huge fangs. These distinctive downward-facing ‘chelicerae’ are shared with its larger, more exotic, arachnid ancestors. The fangs of more modern spiders cross over.

In spring and autumn each year male Purse Web Spiders leave their burrows to go wandering in search of females. This is when you are most likely to find an adult spider. If successful in his quest he tears an entrance in her silk tube and, after mating, the pair will live here together for a while.

In early spring each year juvenile Purse Web Spiders exit the nest burrow and climb surrounding vegetation. They weave thick lines of silk to aid dispersal, and build tent-like structures around which they initially congregate.

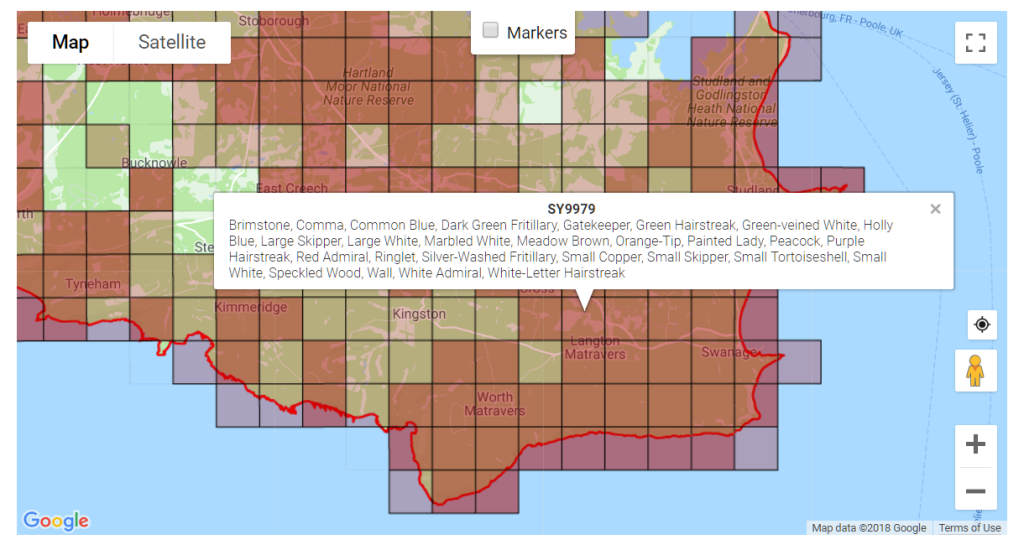

Locating this silk rigging is a good indication that an adult’s burrow is nearby. Look out for it at the top of low gorse or heather on heathland in the south of England from mid-March. This species can also be found on chalk grassland.

In the aftermath of heath fires, discarded sections of Purse Web tubes become more visible. Heat damages the surface layer of camouflage, exposing brighter silk beneath.

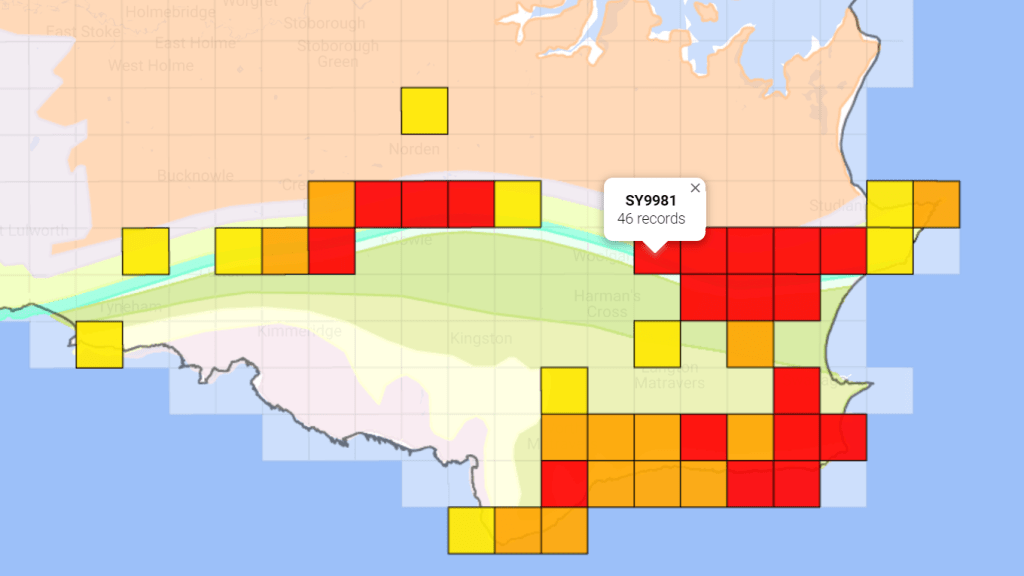

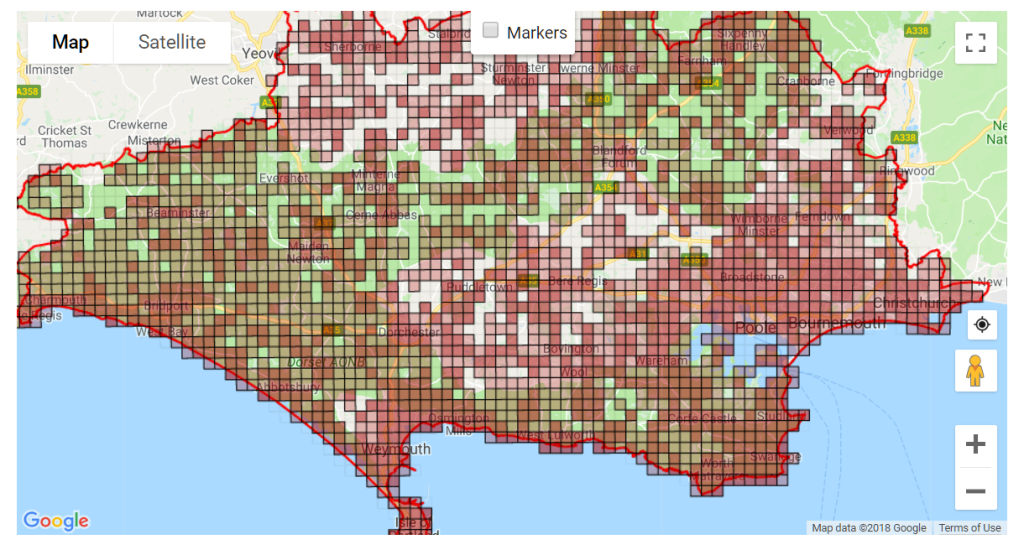

The Purse Web Spider is classified as Nationally Scarce and is Amber Listed. Although it remains widespread, the species has undergone substantial decline. However there is limited data available and so the British Arachnological Society (BAS) has launched a new Purse Web Spider Recording Scheme using iRecord. If you find one of these amazing creatures please be sure to let them know!

Find out more

- Browse and buy Purse Web Spider photos

- British Arachnological Society species profile

- iRecord: Purse Web Spider monitoring scheme